So what does it all mean? – part 4 – Electronic records

In this fourth part of the “so what does it all mean” series I’ll start to bring the paper world colliding with computer technology. As a recap to the preceding parts:

- looked at the design of the paper that GPs have written their records on until recently – the Lloyd George record;

- looked at the content of historical hospital attendance records from Great Ormond Street, and

- then looked at the ReSPECT paper form from the resuscitation society for end of life care preferences

So, in this part, I’ll try to bring this together to form an electronic way of representing the records used in the paper paradigm.

From paper to computer

Recasting the first three parts, we have:

- A generic record model, able to take any records the clinician want to make. This becomes the equivalent of the Lloyd George stationery.

- The content to put into that generic record – the personal record of care for an individual.

- A form design that enables the record keeper to enter the record quickly and easily and encourages an agreed best clinical practice to be followed.

The value of computers

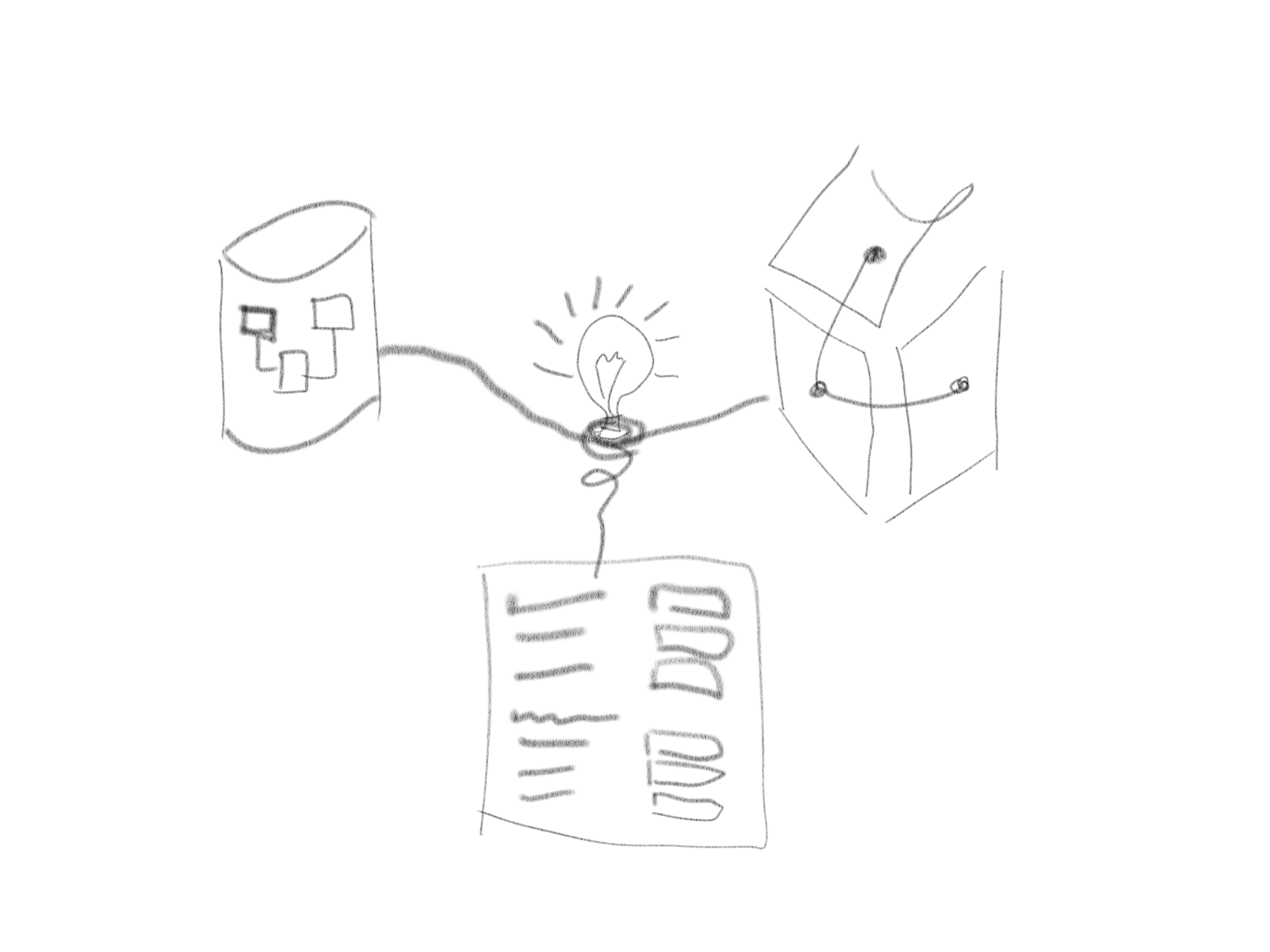

If the computerisation of the care record is to have any advantage over a paper record the computer needs to be more that just a glorified filing cabinet or FAX machine. The value of a computerised care record comes from:

- access by multiple people in different places, settings, organisations, professions and teams at the same time

- an ability for record users to find the relevant information quickly or to be notified of new information in a timely manner.

- algorithms and logic to add value by actively supporting the clinical process as a proactive member of the team, making recommendations, highlighting potential concerns or actively making clinical decisions

If computers are to reach their full value, the care record needs to be in a form that can play to the computer’s strength. A computable care record needs to not only hold the record in a known form (a common syntax) but also to hold the record in a form that is meaningful to computers (a shared semantics). This leads to having a computable understanding of the answer to the title of this series – what does it all mean to a computer?

Towards a shared semantics

Every designer of a record keeping system has to make choices about that design. As a data architect, I’m mostly concerned with the structure and meaning of the record. But that still leaves choices. Should the semantics be in:

- the structure of the database

- the language of the recorded information

- the design of the forms used to capture the record

The structure of the record

I’ve seen all three approaches adopted. Back in the 1990’s the leading system in the UK for recording diabetes information used a Microsoft Access or Microsoft SQL Server data base with a form design that mirrored the database structure. As each community customised the form to meet its own local clinical needs, each database was different. A tick-box on the Microsoft Access user interface form reflected a boolean field in the database. It was a good solution for a community diabetes service but had no easy means to link into any other care record. It became an island of data separated from the rest of clinical practice.

Moving to a common language

I was an NHS hospital’s Information Manager at the time and the database structure made analysis particularly challenging. I chose to migrate the data into a semantic model using a common language rather than a complex structure. The language I chose was Read Clinical Terms Version 3, the successor to the Read Codes used in General Practice. In total I had real-time feeds from eight different clinical systems into a simple common structure with the semantics held in the terminology. It allowed us to bring together a set of very different departmental systems and to provide a coded summary record for clinical and other uses, including payment, quality management and research.

Since the 1990s the health record industry has moved on – the Read Codes have been superseded by SNOMED CT, a clinical terminology formed by melding The Read Codes and Clinical terms Version 3 with the College of American Pathologists’ SNOMED RT product. SNOMED CT is the best example we have of using a common language of healthcare. It’s often described as a “model of meaning”.

SNOMED CT enables rich expressivity by allowing complex concepts to be expressed with multiple codes. In reality it is often used simply as a big list of codes, rather than users exploiting its computational value. This can lead to the creation of local extensions to SNOMED CT with thousands of additional codes to assist data entry.

Alternatively, a bespoke model for each use case

The third approach often used is to create forms (or reports, or interface/messaging specifications) with the context and meaning held in the design of those forms. This approach depends on all the people sharing information having access to the library of forms and a common understanding of the meaning held in the forms’ designs. Often this involves developing an agreement between clinical settings – effectively a contract for specific uses. Examples of this approach include HL7 Version 2 messages, HL7 Fast Healthcare Resource Profiles (FHIR) and OpenEHR templates. Each of these has a core representation with additional specialisations for specific use cases.

In the following articles I will address some of the challenges in having these three approaches co-existing and some techniques and tools to manage those challenges.